#murielle gaude-ferragu

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Over the course of her reign, [Isabeau of Bavaria] started a new fashion for a green lying-in room, a color she particularly liked and which symbolized youth, hope and renewal. Green, which was first reserved for the queen, subsequently became more widely used throughout other aristocratic courts, particularly Burgundy. According to Éléonore de Poitiers, this color was specific to them. Countesses and other great ladies, she wrote, ‘should not have a green room like the queen and the princesses have’."

-Murielle Gaude-Ferragu, Queenship in Medieval France, 1300-1500

#I love that Isabeau had her signature colour#historicwomendaily#isabeau of bavaria#elisabeth of bavaria#french history#fashion#medieval#my post

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

A mother's care : when queens lose their children (XIVth-XVth).

" If most of the queens gave many children to France, death scythed a great many of them. Child mortality was then very high. Generally, three children out of ten didn't reach one year, and almost as many died before puberty. In the aristocratic world, the life conditions of a little prince were of course privileged in terms of food or hygiene, but medicine often was powerless when illness struck. Death happened after strong fevers, epidemics, intestinal problems, or, for the children of Charles VI and Isabeau, various forms of tuberculosis. The numbers are telling: Jeanne de Bourbon gave birth to nine children, but only two sons survived, the dauphin Charles (future Charles VI) and Louis (future duke of Orleans). She saw all her daughters die successively (Jeanne died at four, Isabelle five, Marie six, Bonne and another Jeanne were only a few months old) and one of her sons, Jean. Charlotte de Savoie saw three of her six children die, Joachim (in 1459, a few months old), Louise (in 1460), and François (in 1466, a few hours after his christening).

If the pain felt by the family, especially the mother, is always difficult to evaluate, some clues tend to prove that, far from being "tamed", their children's death deeply affected them. The Religieux de Saint-Denys was touched by the abundant tears shed by Isabeau de Bavière when died her last baby, Philippe, in November 1407. The same way, at the death of dauphin Charles-Orland, three years old, in December 1495, Anne of Brittany was "greatly mourning", with tears and laments. It is true that the expected reactions for a close relation's death were codified (tears, cries, sometimes gestures of distress), and this whatever the actual pain may be. Beyond this normed rhetoric of mourning, we can agree that these mothers' distress likely wasn't completely feigned.

Their children always were buried with care, in dynastic sanctuaries, the cistercian abbeys of Royaumont and Maubuisson, or the Poissy collegiate church, and, from the reign of Charles V, in the royal necropolis of Saint Denis. Two of the king's daughters, Jeanne and Isabelle, rest at his side, just like the sons of Charles VI, Charles who died in 1386 before reaching one year old, another Charles who died at nine in 1400, and Philippe, this newborn who lived less than one day. In the second half of the XVth century, the sanctuaries of the Loire Valley, where resided the sovereigns and their spouses, were privileged. The sons and daughters of Charles VII rested in Tours, those of Louis XI in Amboise, as well as dauphin Charles-Orland, buried in the choir of the Saint-Martin de Tours abbey's church- today in the Saint-Gatien cathedral.

The memory of the little princes was commemorated by the erection of beautiful graves, whose patrons were most often the queens. These monuments are moving, as much for the beauty and delicacy of the sculptures as for the evocation, because of the size of the grave, of the child bodies they enclose. The recumbent effigy of Jean I the Posthumous (1316), likely made at the request of his mother Clémence of Hungary, is remarkable: the sculptor was able to tenderly render the image of a chubby and smiling baby, gifted with a fine face and lovely curls. The funeral monument sponsored by Anne of Brittany to the workshop of Michel Colombe and Jérôme Pacherot offers the special feature to represent on the same pedestal two children's "stone bodies", those of Charles-Orland and Charles, her sons, respectively dead in 1495 and 1498: the eldest of the dauphins wears the crown, while the youngest is still wrapped in the linens of early childhood. "

Murielle Gaude-Ferragu- La Reine au Moyen-Age- Le pouvoir au féminin, XIVe-XVe siècle.

#xiv#xv#murielle gaude-ferragu#la reine au moyen âge#charles v#jeanne de bourbon#charles vi#isabeau de bavière#louis i d'orléans#charlotte de savoie#anne de bretagne#dauphin charles orland#clémence de hongrie#jean i#charles vii#louis xi#and the children

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: “Queenship in Medieval France, 1300-1500” by Murielle Gaude-Ferragu

This book is part of a series called The New Middle Ages published by Palgrave Macmillan. The series is dedicated to pluridisciplinary studies of medieval cultures, with a particular emphasis on recuperating women’s history, and on feminist and gender analyses. The peer-reviewed series includes scholarly monographs and essay collections. The book was originally published in 2014 in French. It…

View On WordPress

#1300-1500#Angela Krieger#book review#French history#medieval history#Murielle Gaude-Ferragu#Queenship in Medieval France#The New Middle Ages book series

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Powerful queens

“There was a time (between the tenth and twelfth centuries) when the king’s wife acted as a consors regni alongside him, having been delegated a share of real power. During the tenth century, for example, the Queen of West Francia played a real role in diplomacy, as proven by a letter that King Hugh Capet addressed in 988 to Empress Theophano, Emperor Otto’s widow and regent of the empire in her son’s name. In it, he announced that ‘Queen Adelaide [his wife] co-bearer of the royalty with which we have associated her’ would meet with the empress in order to strengthen the pact of friendship that had been concluded between them. Here, the female sovereign appears as a consors regni (even though she did not officially hold the title), associated with the throne and capable of representing her husband in the outside world when wielding public power.

Royal charters equally attest to the Capetian queens’ participation in public affairs. They underwrote numerous acts by their spouses and sons, with 40 royal and seigneurial charters bearing their names between the mid-tenth century and the early twelfth century. On numerous occasions, they gave their consent to royal provisions (approximately 65 times during the same period). As a member of the curia regis, the female sovereign took part in governmental decisions. She was also present during important monarchical ceremonies, assemblies, the crowning of the dauphin and receptions for foreign dignitaries.

During the twelfth century, the reign of Adelaide of Maurienne (wife of Louis VI, d. 1155) and the reign of Adela of Champagne (third wife of Louis VII, d. 1206) in many ways represented the apex of this participation. Adelaide was the only queen for whom the years of her reign were mentioned in the royal diplomas after that of her husband. In total, her name appeared 45 times in the royal charters, attesting to her participation in the kingdom’s affairs. It was notably recorded alongside that of Louis VI on charters guaranteeing churches and monasteries royal protection as well as on acts granting privileges to certain urban communes. Adelaide was also the first female sovereign to issue a large number of acts in her own name, which she stamped with a large diplomatic seal. Adela of Champagne’s reign was equally exceptional. From 1163-1164 and after the death of Louis VII (1180), she granted 110 acts, all of which were passed in her own name.”

Queenship in medieval france 1300-1500, Murielle Gaude-Ferragu

#history#women in history#women's history#queens#france#french history#10th century#12th century#middle ages#medieval history#adelaide of aquitaine#adelaide of maurienne#adela of champagne

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

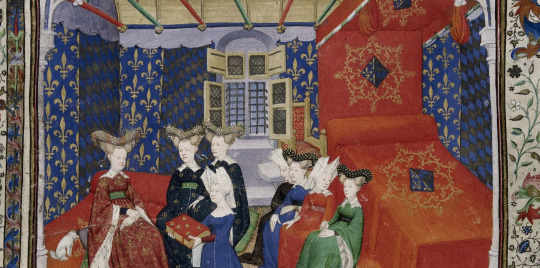

Favorite History Books || Queenship in Medieval France, 1300–1500 by Murielle Gaude-Ferragu ★★★★☆

Unlike her ... rival [Agnès Sorel], Charles VII’s wife and ‘inglorious queen’ Marie of Anjou has remained in the shadows of history. And she is not alone, for most of the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century female sovereigns have been completely forgotten. Except for historians, who still recalls the names of Clementia of Hungary, Joan of Burgundy, Joan of Évreux, Joan of Bourbon and Charlotte of Savoy? Only two queens from this period continue to figure in historical output devoted to the time: Isabeau of Bavaria and Anne of Brittany, the former for the political role she played during the civil war and the signing of the Treaty of Troyes in 1420 (when she became the woman who sold the kingdom of France to the English) and the latter because of her mythologized status as the last Duchess of Brittany, said to have fought to maintain the independence of her principality until the very end.

Further emphasizing the oblivion into which these queens have fallen, no courtly portrait placed them at the forefront of a historical event. The superb iconographical cycle Marie de’ Medici commissioned from Rubens in 1622 to decorate the Luxembourg Palace in Paris and which depicted her triumphant majesty for posterity was still a long way away. Indeed, for some time the easel portrait was reserved only for monarchs in France (up until the reign of Charles VII), but their wives were still rarely represented during the fifteenth century. Only a watercolor depicting a lost portrait of Marie of Anjou is found in the Gaignières collection held at the French National Library.

The memory of these forgotten queens therefore needs to be revived. Even so, such a task should not be about leading the reader through a gallery of individual portraits, but should, more fundamentally, involve examining the nature of their power and their roles within the court and kingdom of France. Well before the time of Catherine and Marie de’ Medici, these women were playing an essential role in the monarchy, not only because they bore the weight of their dynasty’s destiny but also because they embodied royal majesty alongside their husbands.

Indeed, since women were excluded from the French crown in 1316, they could only be ‘queen consorts’, meaning simply the wives of kings. Contrary to other European states, a princess of the French blood could not inherit the kingdom and become a full-fledged queen wielding the complete range of political powers.

... Among other issues, the history of gender has strived to define these plural roles. The place of women in medieval society has never before so thoroughly fed historiographical output on this subject in both Anglophone countries and France. Some authors have focused specifically on ‘powerful women’ in the Medieval West and the notion of ‘queenship’. The queens of France have inspired many studies, which have essentially centered around the Early Middle Ages (see Pauline Stafford and Régine le Jan) or the Early Modern Period (see Fanny Cosandey and Bartolomé Bennassar). However, there has never been a synthesis of these studies that looks at queens of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, which is what this work seeks to examine.

#historyedit#litedit#house of capet#house of valois#french history#european history#women's history#history#medieval#history books#nanshe's graphics

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[OUVRAGE] La reine au Moyen Age : Le pouvoir au féminin XIVe-XVe siècle, par Murielle Gaude-Ferragu ► http://bit.ly/Reine-Moyen-Age Bien avant Catherine ou Marie de Médicis, les reines ont joué un rôle essentiel pour la Couronne, non seulement parce qu'elles portaient les destinées de la dynastie, mais encore parce qu'elles incarnaient la majesté royale #ouvrage #livre #reine #Moyen Age #pouvoir #féminin #Couronne #destinées #dynastie #majesté #royale #cour #royaume #éditions #Tallandier

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

About Marie d'Anjou

Marie d'Anjou owned starlings and parrots, a wild goat, deers and does- in the warren of Montils-lès-Tours- and greyhounds. She was also sent a porpoise. The accounts of her silver in 1454-1455 abounds with details about her hobbies and her tastes. She had spent her childhood sometimes in Anjou, sometimes in Provence, alongside her parents Louis II and Yolande of Aragon, and her brothers René and Charles of Maine. She remained very devoted to them. The gifts she offered on January 1, 1455, were all destined- except for those which were naturally offered to the King and the people of her Household- to her brothers and her sister-in-law Jeanne de Laval. She frequently hosted René d'Anjou, borrowing his boats to go up the Vienne and Loire rivers until Tours. When she fall seriously ill in Mehun in January-March 1455, she instantly called her doctor; she also trusted the Provençal sanctuaries of her childhood and devoted herself to the Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, keeping with her a flask of oil turned miraculous by contact with the local relics. The accounts also reveal that she hadn't forgotten Provençal flavours either: for her Lent of 1455, she at great expanse had brought, from Montpellier to Mehun, olive oil, cumin, anchovies, figs from Marseille, grapes from Perpignan, tuna, and capers.

Murielle Gaude-Ferragu- La Reine Au Moyen-Age- Le pouvoir au féminin XIV-XVe siècle.

#xv#murielle gaude ferragu#la reine au moyen age#marie d'anjou#queens of france#we just know so little about her i was delighted to find this

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Educating the princesses

“All of these princesses, both foreign and French, had received a first-rate education. Some were raised at the French court from childhood, such as Philip IV’s wife Joan of Navarre and Charles VIII’s young fiancée Margaret of Austria. Others were educated within their own families in their respective principalities.

Educators had long debated what women should be taught. In 1265, Philip of Novara had advised against teaching girls—except for nuns— how to read and write. He was, however, in the minority. Far from being neglected when it came to aristocratic education, women were the recipients of veritable miroirs aux princesses (didactic works presenting the exemplary image of the good ruler or, for women, the ideal princess), which reveal all the care that went into their training—as religious as it was moral and intellectual.

(...)

Beyond these theoretical treatises, sources on the practice of that time provide information about the educational methods of the period. Young princesses learned to read and often write. Such instruction often took place within the palace under a tutor. At the court of Savoy in the mid-fifteenth century, Pierre Aronchel was the schoolmaster of Louis and Anne of Cypress’s eldest daughters Margaret and Charlotte (future wife of Louis XI).

Like their brothers, young princesses first learned reading and religion. They learned to read using an alphabet book (Margaret of Austria learned the alphabet using a book handsomely bound in black velvet) and continued with psalters and books of hours. At the age of seven, young Joan of France, who was married to the Count of Montfort, received a richly illuminated book of hours of Notre-Dame from her mother Isabeau of Bavaria. During the fourteenth century, young girls at the court of Savoy practiced reading using liturgical collections, matins and penitential psalms, which were replaced by books of hours in the fifteenth century. Like their brothers, Savoyard princesses also learned to write.

Latin, however, was reserved for boys, which was one of the primary differences when it came to education. Princesses only knew the necessary prayers and formulas for following mass and reading their books of hours. There were a few exceptions nonetheless. Saint Louis’s sister Isabella of France (d. 1270), for example, was reputedly an excellent Latinist.

Failing Latin, aristocratic ladies knew other languages. John II’s future wife Bonne of Luxembourg, who had been raised in Bohemia, spoke Czech, German and French. Yolanda of Bar —daughter of Robert, Duke of Bar, and wife of John I, King of Aragon—could read ‘Limousin’ and Latin in addition to being able to write in French and Catalan. Others had a harder time learning a foreign language. During her entry ceremony in Paris in 1389, Isabeau of Bavaria was criticized for her poor understanding of French—four years after she had arrived in the kingdom.”

Queenship in medieval france 1300-1500, Murielle Gaude-Ferragu

#history#women in history#women's history#queens#middle ages#medieval women#france#french history#medieval history#isabeau of bavaria#Joan of navarre

103 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The female sovereign not only had rights, but duties too. She had to practice the ‘profession of queen’, which was not simply reduced to the acts of procreation and caring for the children of France. Far from being confined solely to the private sphere, she participated in the communication of power, and, as her husband’s corporeal double, she embodied the female equivalent of majesty. At once queen of ceremonies, queen of hearts and renowned patroness, she also contributed to the proper functioning of ‘court society’. Isabeau of Bavaria even played a broader political role due to her husband’s intermittent ‘absences’ (due to bouts of madness).

Queenship in medieval france 1300-1500, Murielle Gaude-Ferragu

69 notes

·

View notes